Memory has changed more in the last 70 years than it has in the last 165,000 years. For the better part of our existence as humans, memory has been something fluid, variable, and socially constructed. The emergence of images and the invention of writing did little to change the way in which we understand our own memory. A heterogeneous group of living narratives that appear and disappear, that constantly mutate and change, that cannot be fixed on any medium. It would not be until the invention of the phonograph, film, and video that human beings began to think about the nature of memory, because although, at first, these technologies seemed like a perfect memory, we soon discovered their plastic and volatile character. From that point forward, the human race was left to reflect—using the phonograph, film, and video—on those objects, people, places, portraits, and stories that we insist on associating with the construction of what we have come to call memory.

Programmer:

DANIEL MONJE

8 SHORT FILMS

1h. 32min. 56s.

RUNTIME

1.

Prisiminimų nešėjai

The Bearers of Memories

—————————————–

Miglė Križinauskaitė-Bernotienė

—————————————–

With every moment – one more memory. But memory sometimes goes blind and what is left becomes hazy.

2020, Lithuania | 13min. 17s.

2.

CICATRIZ

SCAR

—————————————–

Daniela Cáceres López

—————————————–

Video poem made in the quarantine period that explores the encounter of three images of the same person that meet in front of a mirror.

2020, Colombia | 1min. 33s.

3.

Costume Change Forever

—————————————–

John Harlan Norris

—————————————–

Costume Change Forever explores the construction of persona through the lens of animated portraiture. Based on Director John Harlan Norris’ ongoing series of conceptual portrait paintings, the film uses a variety of animation methods to investigate the complicated and relentless task of presenting self at a time in which our likenesses have become increasingly malleable, fraught, and self-searching.

2021, United States | 8min. 28s.

4.

Barokk Femina (Nr.7-11)

—————————————–

Péter Lichter

—————————————–

Adaptation of Márió Nemes Z’s poetry book. Dadaist collage on the contemporary Hungarian collective subconscious (in fragments). Loosely close to Hungarofuturist movement, which “is a cultural-artistic movement that attempts to rethink Hungarian national identity as freed from self-colonizing nationalist narratives. Similarly to Afrofuturism, it forms an identity-poetic experiment in radical imagination, through which an emergent minority identity can feed into a strategy of post-ironic overidentification. As opposed to the hegemonic discourse of Hungarian consciousness, it represents an alternative way of being Hungarian through discovering post-Hungarianness.”

2020, Hungary | 15min. 0s.

5.

SHARITS / KASSEL 2015

—————————————–

Antoni Pinent

—————————————–

A film essay and homage to Paul Sharits that reveals and deconstructs film as an object by studying and entering into dialogue with time, following Sharits’s own thought processes and film/artworks. aka ‘QR CODE / FILM [#1A-#1B]’.

2020, Switzerland | 8min. 25s.

6.

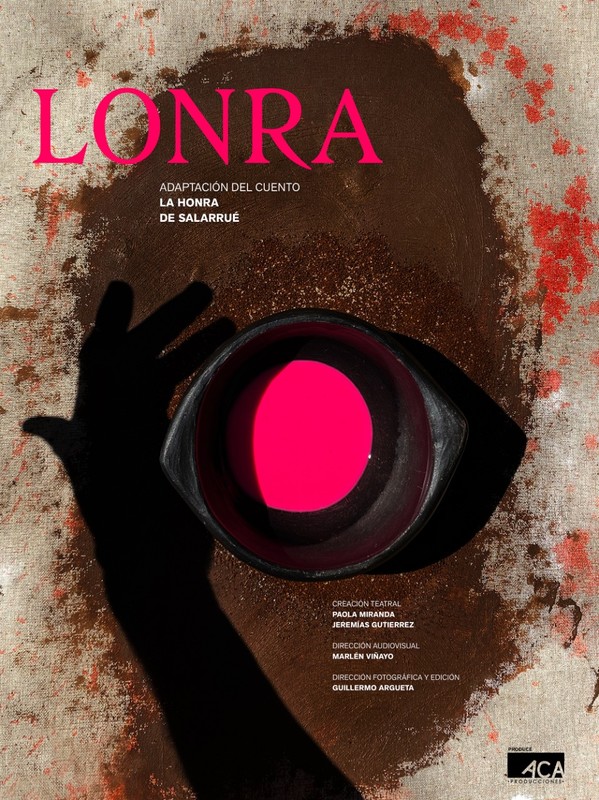

LONRA

—————————————–

Marlen Viñayo

—————————————–

Based on a story by the Salvadoran writer from Salarrue. This isn’t just another story being told in the past. And it’s not a unique story, as, unfortunately, it’s repeated every day. It is a glimpse of the life of a girl, almost a woman, Juana or Juanita, as she likes to be called.

One day on a windy afternoon, her smile was erased along with her childhood. That day her song was no longer being heard and nothing was the same again.

2020, El Salvador | 20min. 0s.

7.

The Beautiful One Has Come

—————————————–

Valentina Ferrandes

—————————————–

Where do historical artefacts belong to? And what do we really mean by “original”? In October 2015, German artists Nora Al-Badri and Jan Nikolai Nelles visited the Neues Museum, equipped with a covert 3D scanner hidden under Al-Badri’s jacket. Using the scans of the statue, they 3D printed a polymer resin replica, accurate to individual chips and pockmarks. They called the project “Nefertiti for Everyone”.“The Beautiful One Has Come” is a time-based, parametric manipulation of Nefertiti’s scans, a contemporary take on an icon feminine beauty and Egyptian heritage appropriated by western cultural institutions.

2020, United Kingdom | 6min. 32s.

8.